Linfield students abused by the same perpetrator say the college’s reporting system failed them

Two Linfield students allegedly assaulted by the same perpetrator say the college must do more to help survivors.

Safety is supposedly a guarantee on a small college campus, but not for two Linfield students who say they were sexually assaulted, stalked and threatened by a peer. They are claiming the college hasn’t done enough to protect them.

This is not the first allegation of sexual assault misconduct at Linfield in the past year. The college just paid AnnaMarie Motis, the former student trustee representative, a $500,000 settlement after she sued for negligence over her alleged attack by former Trustee Chair of Financial Affairs David Jubb. He is facing felony indictment for sexual abuse and is due in Circuit Court for the first time on Wednesday.

Additionally, three students have come forward about their internal assault and harassment cases, and another about reporting on-campus rape through local police.

The Linfield Review doesn’t identify alleged survivors of sexual assault unless they give explicit permission to be named.

The first of the two students said she was assaulted on campus the summer after her freshman year by a Linfield peer who she considered a friend. She reported him halfway through her sophomore year in 2018.

The second student, who said she was sexually assaulted and then stalked by the same aforementioned perpetrator, filed an NCO with Residence Life in October of 2018.

The first student confided in her academic advisor, who encouraged her to report to the administration. She reported to professor Brenda DeVore Marshall, a title IX deputy officer, and then Jeff Mackay, the director of residence life and associate dean of students. Soon after, she filed an NCO against her alleged abuser with Mackay.

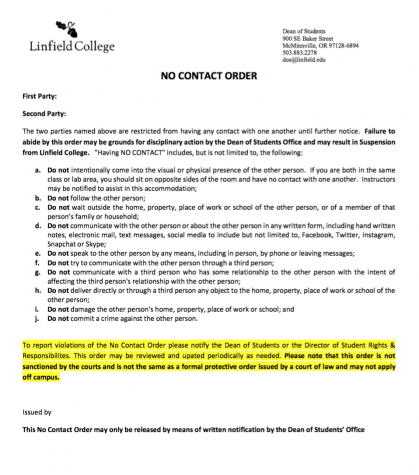

NCOs are informal contracts that the administration offers sexual assault survivors, and also students with lower-level offenses. Breaching an NCO, according to Linfield’s policy, “may result in disciplinary action.”

These orders have multiple demands each party must follow including: not coming “into visual or physical presence” of each other, not following each other, and not communicating with each other “in any written form.”

Mackay said that from 2016 to 2019 there have been on average six to 10 NCOs issued each year, and that one to four of those orders were related to sexual misconduct reports. He stressed that Linfield’s NCOs are not the same as a court-ordered formal protective order and do not specify a certain distance students need to maintain between each other.

The first student said that along with these stipulations, Mackay said her professors would receive an automated email to alert them of the students’ NCO if they ended up in the same class.

However, Mackay said in an earlier interview about campus sexual assault that only Residence Life and College Public Safety know about students’ NCO agreements.

“No contact orders are confidential, however a student can request that certain relevant faculty or staff be made aware of the order if they feel that it will be helpful for them,” Mackay said via email. “If two students with a no contact order are in the same class we will work with the specific faculty member to explore academic measures that will allow the no contact order to be followed.”

The second student said she feels as though her case was mishandled on multiple levels. “First, the lack of education I had meant that I didn’t report as soon as I could have because I didn’t know that stalking could be reported,” she said. The PTSD from her assault caused her to forget that it had happened, so she only reported the stalking.

“My abuser is still on campus, even though I’m not the only person who has come forward against him,” she said. “My NCO was supposed to prevent him from being in my hall, but the fall of 2018 he was consistently in a room down the hall from mine and I could hear his voice. I took the name tags off my door because I was afraid of him knowing where I lived.”

The first student described the reporting process as scripted: that she was told it was supportive and survivor-centric. But she didn’t find that to be the case.

“We’re not supposed to speak about what happened and I don’t agree with that,” she said. “I think that is yet another way the college silences survivors.”

Additionally, she claimed Mackay “heavily counseled” her away from reporting through law enforcement.

The second student also said she was told to not speak of her NCO.

“A no contact order does not prohibit the students involved from talking about the provisions,” Mackay said in an email.

After filing the order, the first survivor also claimed her abuser breached it multiple times. She said he trespassed at her work, attended events she was involved in, and even entered her on-campus residence hall.

Those times when she saw him enter her building through her window, she said she wouldn’t go to class out of fear that he would be waiting for her in the hallway.

“I feel so incredibly unsafe around him, that I cannot be in the same room as him,” the first student said. “That was something I was promised the no contact order would protect me from. Jeff told me that he would not be allowed in my place of residence.”

This student also alleged that her abuser has threatened her and her loved ones with physical violence.

After these instances, she met with Adrian Hammond to discuss the provisions of her NCO, who is the director of student rights, responsibilities, and community engagement at Linfield College.

She said Hammond has aided her in this process. “Talking to her is the first time that I’ve felt support from the administration in any way, shape or form,” she said. Hammond added stipulations to her NCO.

“A lot of us never see those provisions [in the NCOs],” the student said. “There are harsher penalties for alcohol violations than there are for sexual assault. And that’s not right.”

The second student said she doesn’t feel like her NCO has been helpful, and that even after reporting her stalker’s actions to Hammond, nothing changed for her.

“When I provided evidence showing that our story was accurate — Snapchats and texts from friends telling me that he was there when he wasn’t supposed to be — it was not really taken into consideration, even though his story directly contradicted it,” she said.

The first student had planned on transferring schools in the aftermath of her assault, but didn’t because some of her credits wouldn’t have carried over.

The second student wanted to switch colleges too.

“The simple fact is I don’t feel safe on campus and I won’t feel safe until either myself or my abuser are gone,” she said. “I applied to transfer from Linfield because of my assault, but ultimately chose to stay. I would love to see a campus where people feel safe, not only coming forward and reporting, but also just safe knowing that they don’t have to worry about being assaulted on in general.”

“The impact this has had on my education and on my time at college is huge,” the first student said. “I don’t feel safe here, and the college has not done enough to make sure that I am protected, which is really frustrating.”

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has controversially rewritten Title IX rules about campus sex abuse, which is the educational amendment that protects students from gender-based discrimination in federally-funded schools. She released her proposal for the first time two years ago for public critique, and it drew more comments than any other plan in the department’s history at 120,000 total.

The new proposition would create a judicial-like adjudication process, allowing accused offenders the right to cross examine plaintiffs in a live hearing. Furthermore, the definition of sexual harassment is said to be ambiguous according to Anchorage Daily News, “requiring that it be severe and pervasive.” DeVos claims these guidelines will restore fair trials that often disregard accused offenders and favor survivors.

Now, the first Linfield student said she is done working with the administration on her NCO until her abuser violates it again. She said she now feels more knowledgeable about the reporting process, and more equipped to help other survivors.

“I’m not going to let the college dictate how I heal, because the way this has been handled, at least from a survivor perspective, it seems like the college is much more concerned about their image than about their students,” she said. “That, to me, is not right.”

The second student said it’s important for survivors to come forward, even though she feels reporting procedures at Linfield actually force them to relive the trauma of their attacks.

“I think it’s important for people to come forward because I know there are so many people on campus who are also survivors,” the second student said. “Linfield likes to act like assault doesn’t occur on campus when it clearly does, and brushing these cases under the rug benefits only the people perpetrating these assaults.”

***

This story was updated on May 13, 2020. David Jubb was inaccurately said to be the Chairman of the Board of Trustees. He was the Chair of the Financial Affairs Committee.

***

If you have a similar story that you would like to share with the Linfield Review, you can contact Camille Botello ([email protected]), Elin Johnson ([email protected]) or Alex Jensen ([email protected]).

If you or someone you know is a survivor of sexual assault or relationship violence and would like on-campus support, you can reach out to College Public Safety at 503-883-7233, the Student Health, Wellness and Counseling Center at 503-883-2535, or Residence Life at 503-883-5433.

Off-campus resources include the Henderson Hours Crisis Line at 503-472-1503, Yamhill County Crime Victim Services at 503-434-7510, and the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.

rashaad • Apr 27, 2022 at 10:26 am

i love how this gives me a who what when why were