Student says reporting assault to police first helped keep Linfield accountable

Another student has come forward about her experience with sexual assault on campus during her sophomore year. She’s claiming that reporting through the McMinnville Police was more productive than if she had reported to the college alone.

This incident is the third story this year from a current student about how Linfield handled reports of a sexual assault.

The Linfield Review does not identify survivors unless they ask to be named, and never identifies alleged perpetrators if they haven’t been found guilty in a court of law.

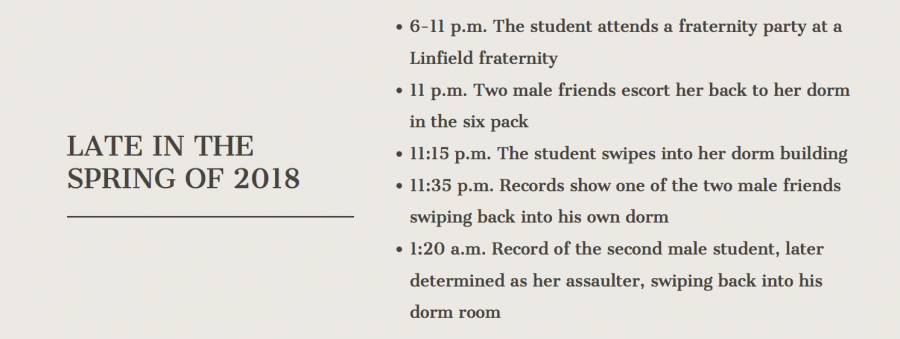

The incident occured with just a few weeks left of spring semester 2018. The timeline is below, with time approximations for reference.

The student reported the assault to the McMinnville police and then went to the hospital at 11 p.m. the next day— about 21 hours after the attack— where she was tested with a rape kit.

“I went to the hospital. I let them poke me, prod me, touch me, do anything they wanted,” she said. “At that point I was just so tired that I didn’t really care what they did to me anymore.”

DNA evidence was found in multiple places on her body and by the police in several parts of her room. With this information police deduced the perpetrator was the man who walked her home from the fraternity house and stayed in her room after the other male student had left.

Linfield Residence Life allowed the anonymous student to move in with a friend after the incident. She said she no longer felt comfortable in her room, which had become the scene of a crime.

“I think because I took legal action first, before I went to the school, the school was a lot more willing to do what I wanted,” the student said. “After talking to a lot of people, they’ve said that the school often wants to just brush it under the rug … so I think because I went the legal route first they kind of felt pressured into following suit.”

“A student is able to report to McMinnville police, Linfield College, or both,” Jeff Mackay, director of residence life and associate dean of students, wrote in an email on behalf of the Linfield administration. “If a student chooses to report with McMinnville police, their criminal investigation process may require the college to delay their investigation to ensure that it does not interfere with a police investigation.”

“I’ve definitely heard rumors that if you go straight to the school, they’re going to try to do everything they can to make you feel comfortable but won’t actually go forward with anything,” the student said. She said she decided to report through law enforcement because she worried Linfield would be “more concerned with keeping him safe than getting rid of him.”

The student said that the attacker’s desire to go into a profession where he would work with children was her “biggest driving factor” in going forward in taking legal action against him.

The student reported the assault to the college two days after she went to the police, and College Public Safety officer Dennis Marks sent out a campus-wide email the next day reminding students to not let unknown people into residence halls. At this time the college did not know who the perpetrator was. It took less than a week for the college to deduce who could have assaulted her.

“Criminal matters are handled by local law enforcement,” Mackay wrote.“If the reporting party chooses to pursue a formal investigation through the college, the college would follow its own investigation process.”

In her official testimony to the police, she said the memories from the night of her assault came rushing back to her.

“It’s a little scary how your brain just chooses to stop remembering it after awhile,” she said. “But if it comes up, it will remember it all. There was not a single detail that I do not remember of that night when I gave my testimony.”

“I had remembered almost all of it, down to some very little things that seemed so small,” she continued. “As simple as feeling his facial hair on my forehead when he left. Things like that are things you choose to forget. You remember what it felt like, you remember what it smelled like… You remember all of this. And I think that was probably the hardest part.”

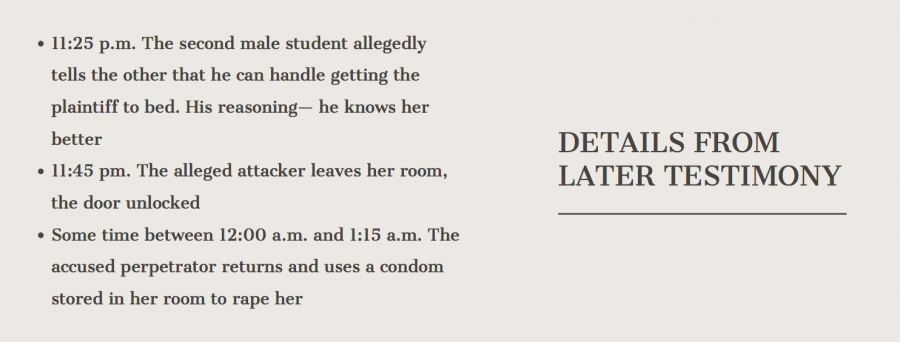

At first the survivor didn’t know who attacked her. She had heard her door close and then reopen shortly after, so she assumed the friend who had walked her home left and someone else had entered.

All the lights were off so she only saw a “dark, shadowy figure” in her room. She said that when he was raping her she buried her face in her pillow so she wouldn’t have to acknowledge how he was violating her.

She said she did not want to admit to the idea that someone she knew, who was her friend, could have done this to her. According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, 39 percent of sexual assaults are committed by an acquaintance.

“He was someone who I had really allowed into my life and I didnt want to believe that someone I trusted could do something so horrific,” she said.

The student said the college found “more than enough evidence on their own” using her statement and swipe card access records to find that the alleged perpetrator was guilty.

“We have used card access records as evidence. The investigation would use any relevant evidence that would be presented,” Mackay wrote.

The DNA taken from three different parts of her room and six parts on her body show there is substantial biological documentation on record. The McMinnville police have the attacker’s confirmed DNA evidence and are prepared to use it as evidence against him in court.

In the fall of 2018 after she had returned to campus, Mackay had a meeting with her to check in and inquire about the police investigation, and to discuss the no contact order (NCO) they issued. She had several more meetings with Mackay in the spring of 2019 about the campus investigation and the status of her alleged attacker’s enrollment.

“Jeff was always very concerned about where the police were, what they were finding out, and the next steps,” she said.

The student said the college filed an NCO on her behalf, telling her it was their typical procedure. Her NCO did not indicate a distance her attacker had to maintain from her, but outlined how he was not to communicate with her in any way. She said she thinks this was in part the police’s doing because they didn’t want the two students to interact while there was an ongoing police investigation.

Mackay said that from academic years 2016 through 2019 there have been on average six to 10 NCOs issued each year, and that one to four of those orders were related to sexual misconduct reports.

The alleged offender left Linfield due to the possibility of expulsion; the administration had more than enough evidence to attach him to his crime. He is banned from campus unless he completes the campus investigation in part through the student conduct board.

A Linfield student is alleging that McMinnville Police held the college accountable for the duration of her sexual assault case.

She said that currently the case is pending trial and the accused offender is facing 11 charges including sexual assault in the first degree without consent, sexual assault in the first degree by force, rape in the first degree, and multiple sodomy charges. Each act of non-consensual penetration was treated as a separate charge.

“I also don’t think people realize there’s a difference between force and no consent,” the student survivor said. “Not only did I not give my consent, I was held down, so those are considered two separate charges.”

April is Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month. The #It’sOnUs movement — which Linfield is a part of — states that one in five women and one in 16 men are sexually assaulted while in college.

The Linfield Annual Security and Fire Safety Report showed that in the 2018 academic year just one incident of rape was reported on the McMinnville campus, compared to two in 2017 and three in 2016. Linfield, like all colleges and universities in the United States, is federally mandated to make public all reports of crime under the Clery Act. Additionally, Linfield’s CPS publishes a weekly incident log for the McMinnville campus online every Friday.

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has been controversially changing the federal requirements that establish how colleges and universities respond to allegations of sexuall assault, doing away with Obama-era policies. She is creating more rigid, narrow definitions of misconduct, and allowing witnesses to be cross examined. Survivor advocacy groups have criticized the changes, while men’s rights organizations have heralded them as restoring due process.

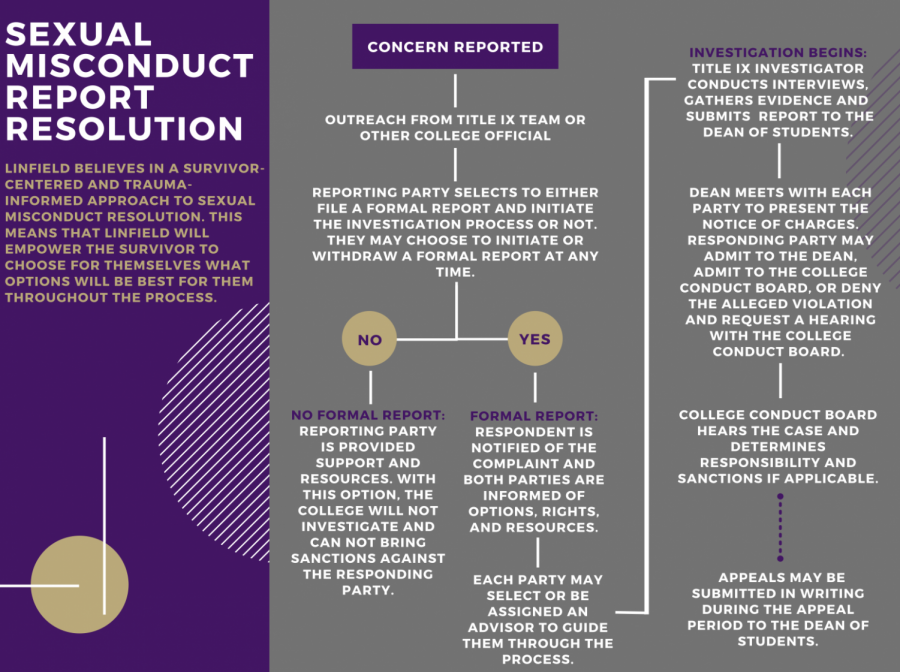

“Every student has a right to due process,” Mackay wrote. “A formal report starts an investigation, which can result in a hearing where the College Conduct Board will determine if the student is responsible for violating a policy and what appropriate sanctions should be issued.”

The student said that after her assault she continued to see an on-campus counselor she had been seeing prior. Additionally, she had a survivor’s advocate — unaffiliated with Linfield — attend some of the meetings with police to ensure she was being treated fairly. Now that she is in the trial phase of the legal process, there is an attorney responsible for her case.

“The school didn’t do a whole lot financially. They did not ever offer to pay for my counseling,” the student said. “It’s frustrating that I’m going to that for something that happened on their campus, by one of their students, in one of their dorms, and they aren’t willing to waive that fee. You told me to get help, but you aren’t willing to financially support that help.”

For this student, campus hearsay about the reporting process made her wary about trusting the college with her report: “The rumors I’ve heard is that if you’re drunk, they’re [Linfield] less likely to go forward with things because there could have been implications that you made it up, or that you had actions that could have led someone to believe that that’s what you wanted.”

“We would encourage students to report so that we can work together to determine why they are feeling unsafe and help develop ways to facilitate their ability to feel safe,” Mackay wrote. “We could help students to explore obtaining a protective order from the courts, if this would help them to feel more safe.”

“I don’t think I would be as okay as I am without having gone the legal route,” the student said. “If I would have done anything differently, I would have gone sooner. I don’t think the police gave [Linfield] a whole lot of leeway into letting this go.”

***

Update on May 1: According to the McMinnville News Register, the accused perpetrator was formally charged for sexual assault on December 18, 2019 and was booked in the Yamhill County Jail on $50,000 bail. The former Linfield College student is facing 11 charges of the 17 previously stated: one account of first-degree sodomy, four counts of first-degree unlawful sexual penetration, four counts of first-degree rape, and two counts of fourth-degree assault.

According to the Yamhill County District Attorney’s Office, the accused assailant is currently out of custody and is next due in court on June 18. If he is found guilty of the charges as they are stated, they will fall under Oregon’s Measure 11 mandatory minimum sentencing law: he would serve a minimum of 100 months (about eight years) and not be eligible for probation, parole, or early release. An Oregon judge could also determine whether he serves his time for separate charges concurrently or consecutively.

***

Editor-in-Chief Alex Jensen and News Editor Camille Botello were reporting contributors for this story.

If you have a similar story that you would like to share with the Linfield Review, you can contact Elin Johnson ([email protected]), Camille Botello ([email protected]) or Alex Jensen ([email protected]).

If you or someone you know is a survivor of sexual assault or relationship violence and would like on-campus support, you can reach out to College Public Safety at 503-883-7233, the Student Health and Wellness Center at 503-883-2535, or Residence Life at 503-883-5433.

Off-campus resources include the Henderson Hours Crisis Line at 503-472-1503, Yamhill County Crime Victim Services at 503-434-7510, and National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.