Through the eyes of Theodore A. Harris

October 19, 2021

After over four years of hard work and communication, the Linfield University Miller Art Gallery was finally able to unveil its latest guest-artist exhibition. “Theodore A. Harris: Art as Social Praxis” opened Oct. 11 and runs through Nov. 26.

“It is an honor to have him here. His work is an inspiration to all,” said Allison Hmura, a sophomore studio art major.

Harris hails from Philadelphia and flew to Oregon to showcase his work to the Linfield community. He is the founder and director of The Institute for Advanced Study in Black Aesthetics. In addition to art, Harris boasts an impressive list of published books that he has co-authored.

Linfield’s gallery originally planned to host Harris’ work in 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic postponed it. This exhibit is composed of three series: “Collage and Conflict”, “Surgeon General’s Warning” and “Thesentur Conscientious Objector to Formalism”. This gallery was curated by Thea Gary and Brian Winkenweder who both teach art at Linfield.

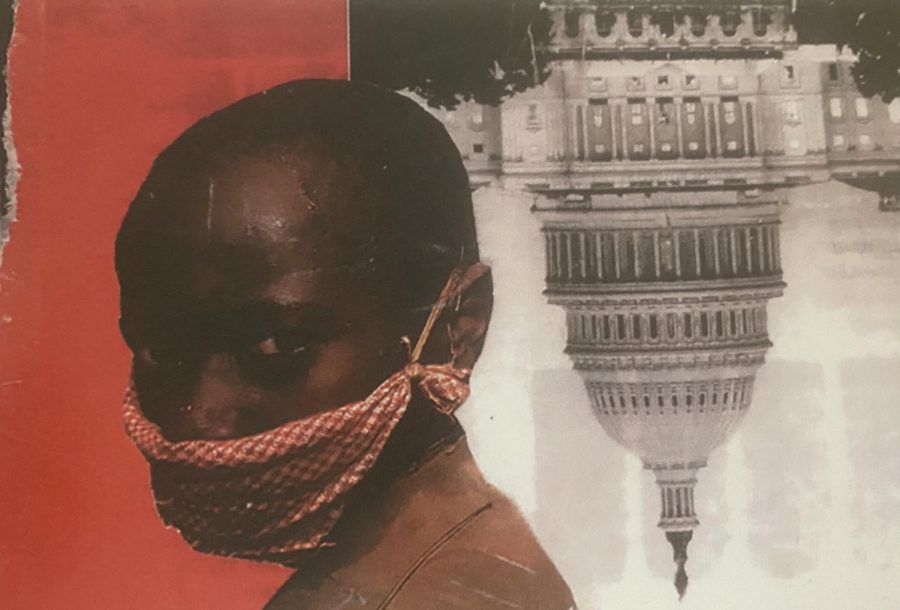

The 27 pieces featured in this exhibit showcase a wide variety of mediums and techniques. Harris includes everything from bold text in a stark white box that replicates the surgeon general’s warning featured on cigarette boxes, to multimedia that features provocative collages.

In addition, the exterior of the fine art buildings now display huge floor-to-ceiling murals of Harris’ smaller works that were installed with the assistance of Chip Thomas, a fellow east coast artist.

Each series in the exhibit is accompanied by poetry manifestos written in conjunction with the creation of the artwork. In the “Collage and Conflict” series, Harris wrote the manifesto in three parts to parallel the triptych nature of the series. A triptych is a picture or carving composed of three smaller panels placed side by side. All pieces in this particular series feature three multimedia collage pieces framed together.

“I wrote the manifesto to describe every series that I create,” Harris said. “The words describe the things [I] want to see in the work, maybe a list of materials. I turn that list into poetry, into a manifesto, that kind of gets unhinged like a manifesto should.”

The manifesto is a reflection of Harris’ vision. Much like his work, it is the rawest representation of his perspective he can offer. Listening to his poetry and looking at his work is as if he carved out his eyes and provided them to his audience so that they may see society as he does.

“The content [of the manifesto] is about how I feel about the work, how I feel about the subject matter, the content and form, and what I’m trying to do with it,” Harris said.

Through his art and accompanying poetry, Harris comments on social inequities and pokes at the holes in white histories. He is, in the simplest terms, a rebel. His art is fluid and unrestrained, it invades all layers of protection the viewer has. There is no shield from his raw and unfiltered message, but when confronted with the complicity the viewer might have in these social injustices, they may feel a necessary guilt. That is the very essence of Harris’ work.

“Art is inexorably infested with guilt. Yet this does not release art from the necessity of recalling again and again that which can survive even Auschwitz and perhaps one day make it impossible,” Harris said.

His artwork confronts many social issues in an intersection of art and politics. His art even calls attention to the politics of art. The not-so-subtle subjugation of minority artists throughout history.

This gallery is dedicated to the late art historian, David Craven. Craven died in 2012, but throughout his career he proved to be a force for social equity in and out of the art community. As such, Craven deeply admired Harris’ work and often aimed to boost the voices of minority artists.

“Craven was deeply committed to social democracy and an unwavering belief in the ability for art to create a more just, humane and caring world,” Winkenweder said.

Clearly, the admiration was mutual. Craven’s critiques complemented both Harris’ messages and the means by which he conveyed them. And now Harris has gone and honored Craven in the best way an artist can: by creating and sharing art in Craven’s name. Harris’ work may investigate the nature of oppressive forces on individuals within a society, but it also acknowledges the (albeit small) strides the world is making to a more equitable society .

In fact, collages are one of Harris’ go to mediums because “it means to create a new world with an existing world,” Harris said.

The concept that true freedom and social equity may be built with tools already possessed is inspiring. Brick-by-brick and line-by-line, it is possible to deconstruct systems that are beneficial to the few, and rebuild society to be its kindest, most equitable self.

Harris is a rebel and a humanitarian. He is a force for destruction and a visionary. While his work conveys the gravity of the oppression society faces today, it also makes a better future seem possible.

The last day to see Harris’ work in person is Nov. 11.

“Everyone should go to his exhibit. His way of looking at the world is enlightening,” Hmura said.

Stephen Louis Paulmier • Oct 24, 2021 at 1:51 am

It is welcome news to read this notice of a most appropriate recognition of this artist by the scholars at Linfield University. As a long time admirer of Theodore A. Harris I am deeply moved by the respect these curators have shown in the planning and execution of this show. The fitting tribute to the late master of contextual clarity and artistic gravity David Craven finds this University setting quite the example for students and working folk to engage together in the production of a new and more just paradigm. I hope I get the opportunity to experience this courageous initiative in person, thanks to all who’ve made it possible.