Girl in Journalism

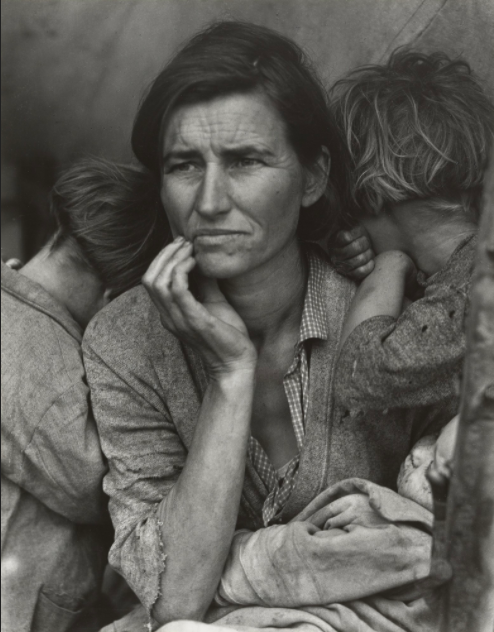

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California March 1936. By Dorthea Lange. From the Museum of Modern Art http://www.moma.org

April 5, 2021

Click. Whiiirrrrrrr. Click.

I bought this old film camera on a whim. I’m pretty sure I woke up that morning, thought it would be cool to have one, and by late afternoon I had plunked myself down on a curb, marveling over the hunk of metal in my hand.

In my mind, I could never learn the true artistry of photojournalism without first understanding the history behind the craft and using a “real camera.” But in reality, I could never learn the true artistry of photojournalism without first recognizing those who came before me.

Dorthea Lange is not necessarily a household name (then again, most journalists’ names aren’t), but her pictures are.

Many people have seen Lange’s Migrant Mother in history books or museums, and it’s not hard to recognize it or her other work as “great.” But what makes it great?

(There has since been controversy over Migrant Mother and whether Lange correctly represented the subject of the photo.)

I sat myself down with Lange’s pieces and I truly studied them. Why was I so moved by a subject’s eyes? How does she capture a whole story in a single frame? How can I read an entire history book without even a word?

Lange, who lived from 1895 to 1965, captured the world as she saw it. She didn’t view her work as art, she viewed it as a vehicle for social change. She told the stories of farmworkers during the Great Depression, Japanese detainees during World War II, and more.

“How could I make something like that?” I wondered each time I popped a roll of film in the camera.

Click. Whiiiirrrr. Click.

None of my photos have people as subjects, mostly because I’m shy, but I tried to capture the same sort of history in one shot using the world as it was around me. I set out to explore– what can I show in my photos? What is the state of McMinnville? How can I show it?

I began to see that the title of a piece can be as important, if not more, than the work itself. I admired Lange’s short, to-the-point titles. A title can provide context or the frame of mind to think of something with. Unemployed Farmworkers, Stockton, California? Without the title, it would just be a man lying in the street.

Lange was a ground-breaking photojournalist. Not just because she was a woman making history in a time when that was an exception, but because her photos helped change the course of history by bringing attention to the issues around her.

As Women’s History Month drew to a close this past March, I spent some time reflecting on the journalists and/or that paved the way before me. And I am lucky to have Lange, as well as others, as an inspiration to both ground-breaking and glass-ceiling-breaking.

Click. Whiirrr. Click.

I guess I’ll just have to keep shooting.