Linfield non-voters align with national trends

January 19, 2021

The nation’s youth population mobilized this election cycle, with an estimated 51% of eligible 18-29 year-olds participating, compared to 44% in 2016. However, not everyone felt the same civic desire that resulted in a record-shattering number of votes for each candidate.

Non-voting Linfield students are a silent group on a traditionally liberal campus. This includes a student from California, who anonymously expressed frustration with the voting process. “Being from California, which is almost an exclusively Democratic-leaning state, I know my vote isn’t going to make a difference, regardless,” said the student.

Linfield University, an institution with a higher than average population of active and registered students voters, also has a significant number of students who choose not to cast their vote every other November. For the most recent comparison, only 52.9% of Wildcats voted in 2018’s midterms. Among the remaining non-voting students, reasons for the lack of voting motivation closely follow national trends. Midterm results are a different entity than presidential races, but can be a decent indicator when evaluating an area’s trends in participation.

In an effort to close the gap between college-aged voters and non-voters, Tufts University’s Institute of Democracy and Higher Education has a program to encourage civic participation at over 1,100 colleges and universities around the nation, including Linfield.

The program, called the National Study of Learning, Voting and Engagement (NSLVE), gathers statistics for participating institutions, helping schools see voting rates and compare the numbers to years past. These measurements give administration an insight into one aspect of student civic engagement, encouraging them to use the information to shape curriculums and campus events.

Part of the job of higher education is political learning, civic learning and democratic engagement, according to IDHE’s Director of Impact Adam Gismondi. “When we talk about democracy, we talk about an aspirational version of democracy,” said Gismondi. “It’s what we strive for as an office and it’s what we think colleges and universities should be thinking about when we’re saying that we want a society that is effectively governed, equitable, participatory and that people are well-informed as a populus.”

2020 election results won’t be finalized for a while, which means that it will be well into next summer until NSLVE has the ability to concretely determine how student populations fared at the polls. For now, they estimate that around 52% of voting-eligible 18-29 year olds in the nation cast a ballot in the 2020 presidential election, an increase from around 44% in 2016.

“The youngest cohort of people in the US right now is our most diverse ever,” Gismondi said. “So, if we want our representatives to represent the issues we care about and look more like the people in this country, it’s important for the people of this country to equitably participate.”

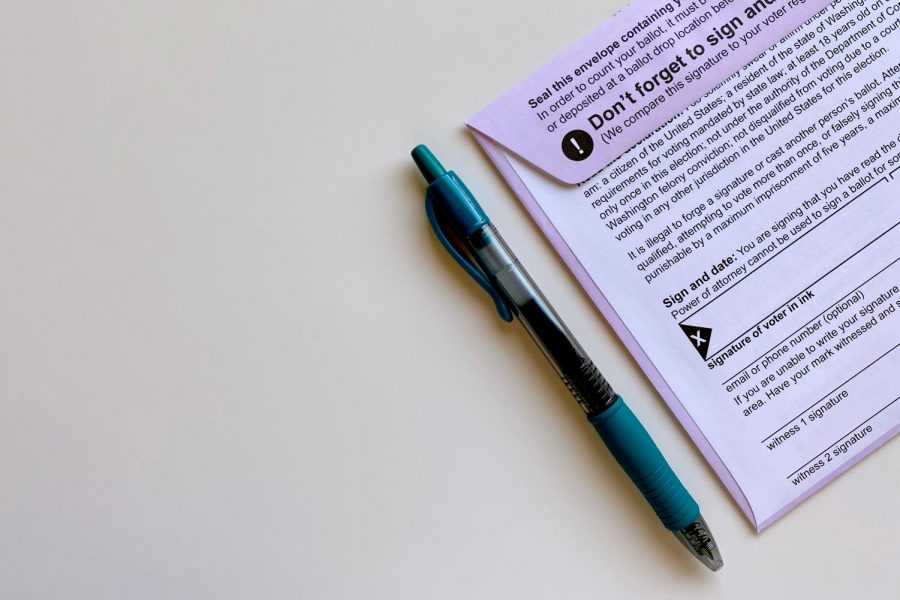

Generally, there are two groups of barriers for non-voters, according to the institute. One of which is structural barriers that affect voting numbers. This can include places with voter suppression, intimidation and where it is simply difficult to vote. Luckily for Oregonians, the state’s mail-in ballot system makes it one of the easiest states to vote in.

Another uniquely 2020 structural issue is COVID-19 concerns at voting booths. People concerned for their health or who failed to plan ahead may have also contributed to vote totals.

More commonly, motivational barriers prevent people from casting a vote. “Motivational barriers are when students might say, you know I care a lot about the issues, but I don’t believe in either of the parties, there’s no one there that I can cast a ballot for,” Gismondi said. “Those are certainly arguments that are worth having, and a college campus is the perfect place to be having them.”

In an incredibly politically-driven year, students may have simply grown weary of the perpetual onslaught of information. “This year there is certainly a question of exhaustion,” Gismondi said. “There have been years that have been politically active, but in my lifetime I think the last four years have been the most constant barrage of news around politics that I’ve ever seen. It’s been hard to keep up with the news, so it’s not hard to imagine that people start to tune out at this point.”

These national trends are just as prevalent at Linfield. In an informal survey on The Review’s Instagram page, 96 followers answered that they voted in this election cycle. Only two respondents said they chose not to vote, raising questions of potential correlation between news consumers and voting practices.

Another Linfield student, who wished to remain unnamed, cited motivational barriers as her reasoning not to vote in the recent election, with a lack of information and societal pressures as the main issues.

“Mostly, I didn’t feel informed enough to vote. Without a fully developed opinion for any candidate, it didn’t feel right to vote for either side,” she said.

Pressure from those around her also prevented her from making a decision. “If I went back to my hometown and my friends and family found out I voted for Biden, it would be a really big deal. The area is pretty heavily Trump supporters,” she said.

But here in McMinnville, she was surrounded by roommates and friends who were passionately voting for Biden and against another four years of Trump. “Not that anyone would have actually been confrontational if I were to have voted for Trump, but it definitely would’ve felt weird,” she said. “I generally tried to stay out of conversations with my roommates who were extremely anti-Trump, just because I didn’t have a firm opinion either way.”

Even now, right before the inauguration of president-elect Biden, data will continue to come in and clue us into voting trends. Official confirmation of the outcome and analysis of Linfield’s results from the Institute of Democracy and Higher Education won’t be available until at least the middle of next year. Until then, we won’t truly know how Wildcat voters fared in the polls.

Raymond Lee Sifdol • Jan 30, 2021 at 10:55 am

Hi Linfield Students

My name is Raymond Lee Sifdol, and I graduated from then Linfield College in 1961. During the first Semester of my Senior Year at Linfield I had the great pleasure of voting for John F. Kennedy in the U.S. Presidential Elections. Most of my fellow students who were eligible to vote in 1960, voted for JFK. Not voting, if eligible, was not an option back then.

Of course JFK was a very appealing candidate, and most young people “back in the day” thought he would make a really good President. Life seemed to be a lot more simple back in 1960, or so it seems. Of course hindsight is always 20/20 vision, isn’t it?