Q & A: English professor explores family, class in Oregon Book Award nominated poetry collection

February 5, 2017

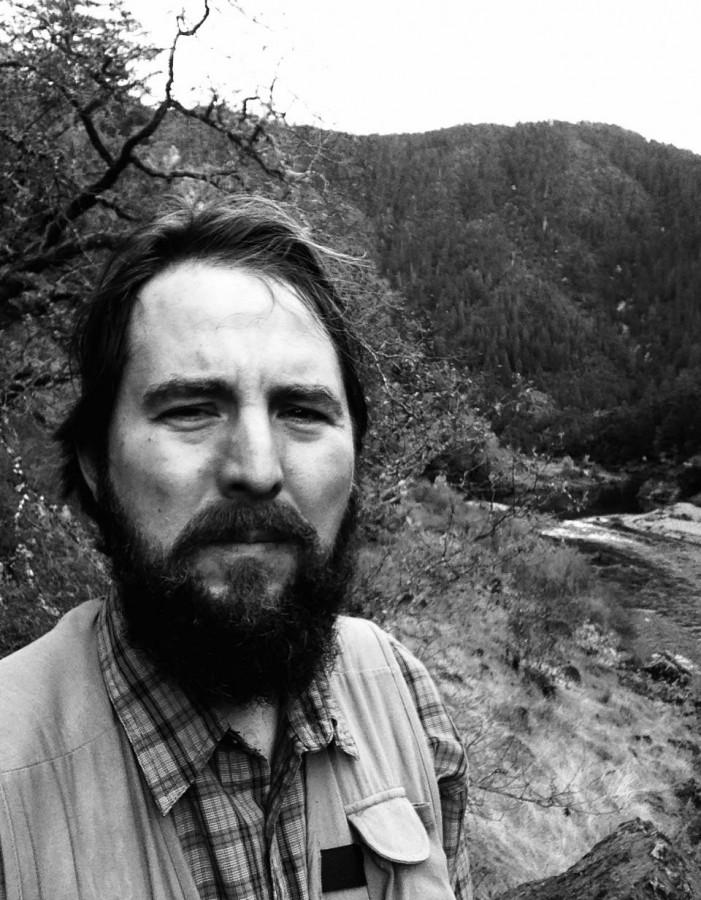

A Linfield English professor’s collection of poetry has been nominated for an Oregon Book Award in poetry.

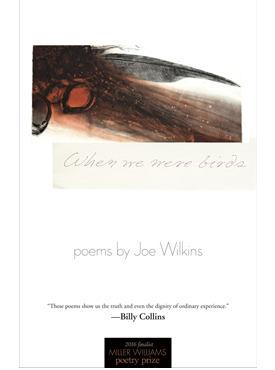

Joe Wilkins, associate professor of English, is one of five authors nominated for the Stafford/Hall Award for Poetry for his collection of poems “When We Were Birds” as part of this year’s Oregon Book Awards. The Oregon Book Awards is celebrating its 30th year and recognizes Oregon writers work in poetry, fiction, nonfiction as well as in young adult and children’s literature.

Wilkins is the author of two other books of poetry and a memoir that have been nominated and won numerous awards.

Wilkins 2016 collection of poems “When We Were Birds” has been nominated for an Oregon Book Award.

Winners will be announced on Monday, April 24, at the Gerding Theater at the Armory in Portland.

What is the genesis of this collection?

This collection of poems grew out of our move to Iowa and being in a new landscape, being in a place we didn’t know. We didn’t know a lot of people and that sort of experience of displacement and trying to find your way, trying to figure out who we were when we were there. A lot of the poems in this collection are in other voices – voices I was hearing as I was going about my day – sort of taking on this other way of looking at the world and speaking. When we were in Iowa we got pregnant. Much of the collection is sort of thinking about this new thing that is coming into our world, this new way we’ll have to be. A lot of the poems are dealing with trying to understand that, trying to reckon with that, and then suddenly there’s this little person here. Those are two things that were happening and then as I started writing I realized these two things are part of the same project.

What sort of themes and ideas are you exploring in your work?

I’m always working with class – ideas of privilege, poverty, and how our way of experiencing the world is so influenced by class. I’ve seen that in my own life and I’ve seen that in the lives around me. The book is reckoning with my own autobiography and my own background of poverty but also then when I’m in the small Iowa town we moved to right as the great recession kicked into high gear.

A good chunk of the town was employed my Winnebago Industries – a big manufacturing place. Many people were fired or for weeks on end were furloughed. It was a huge, huge hit to the town. To see that economic instability – I both knew it and I was seeing it in a new way again, especially as we were getting ready to have a child. It also deals with ideas of the other and how we might be able to move closer to them and to see them as the self, potentially. A lot of the poems that speak in other voices try to do that – to try to see the other as the self and to try to see the self in the other, that sort of radical empathy. There’s also in this book a lot about inheritance: what we get and then what we pass down – for good and ill. What we get from our culture, from our parents, our landscapes and then how those things whether we want to or not, we give to those who come after us. The ways we inherit the world, and the ways then that we might hopefully take what is best of that inheritance and lose some of those things that are destructive.

Can you talk about the title of the collection and why you chose that?

JW: It comes from the first poem in the book. I tell my kids this story most nights. One night my son was half asleep half awake and I asked him what kind of story he wanted and he said tell me the story about when we were birds and I thought of wow oh my goodness and so I tried to tell the story that night. The very next morning I started writing a poem with that title. That poem was one of the last ones that was written and was actually written here when we got to Oregon.

It was one of the last poems that made it into the book and one of the reasons it felt like it sort of encapsulated the book is this sense it’s this poem about what we can be, the beauty that we are and the beauty that we see, the beauty in the world around us – its strangeness – but also then the ways the world works on us and the ways we might choose to be in it. In the end we can choose love, despite circumstance even when they get really terrible we can still choose that.

What are some of the through lines that connect your poems?

Some of the narratives. You sort of see a speaker very much like me in there. You see some of these poems that have similar titles – “Notes to my unborn son” and then I think these voice poems as well. We have these other people speaking into the experience and I think those poems for me sort of were to be able both to speak and to step back and try to say something else – to try to let this other character have their say.

What does your creative process look like?

For the most part I start with an image or a sound, sometimes in a narrative though often narrative ends up in prose. I am interested to inform a lot. I’m always on the lookout for form, I’m always trying to pay attention to it as I’m writing so it’s sort of two things: you have a little bit of an idea, an image or two, a narrative, and then you’re thinking about form and these aren’t working against each other but they’re bumping up against each other and in that kind of collision something starts to happen on the page and you find a language, you find the way the poem needs to go, you maybe discard some things that you thought might be important but are no longer important.

Who are some poets and writers you admire or who have influenced this collection of your work?

My graduate school mentor Robert Wrigley is a constant inspiration. He’s moved in some different directions and I think they’ve all been fascinating and sort of watching him change and grow as a poet has influenced my own growth and in this book I see it’s definitely a growth from the first two and so that sense of movement of being willing to try different things and speak about different things I think is from him a lot. I was actually reading a lot of James Baldwin – not a poet but an essayist and writer. What I admire so much about Baldwin is his ability to see even in the midst of catastrophe and tragedy to see clearly and to speak clearly and to always keep the other in mind. His ability to speak outside of his own experience, though he speaks inside of it a lot too, I find profound. He’s someone who influenced sort of the ways I was trying to speak outside of my experience in this book. Another poet who was influential in this book is Amy Nezhukumatathil. She’s both a really fun, funny poet, she’s accessible, which I admire. But she also writes about parenthood a lot – both the joys and travails and is honest about it and so her work has been an influence as I’m in that same space.

Quite a few of your poems start with “Notes to my unborn son” – can you talk about why that is?

It started as kind of a challenge when I found out we were pregnant. Every day I tried to write a short note. There’s not nearly as many as that in the book so a lot of them didn’t necessarily go anywhere or they were folded into something else but some of them, some of those notes, started to become something and started to cohere and stick together and they became things I did want to say to this new person coming along.

When were the first and last poems composed?

Many of them were composed about 7 years ago because my son is seven years old now. I think there were some too that are before that from sort of the years just before we moved to Iowa and the last one is from our first year here. About 7 years of poems roughly.

Your collection opens with a James Baldwin quote. What work of his is it from and why did you choose to lead with it?

That comes from “The Fire Next Time.” That’s in his note to his nephew – “my dungeon shook” when he’s writing about his nephew’s birth and how scared he is for him and the sense that that fear – it’s both the fear of birth – we are all a little scared when someone is being born – it’s a big deal! But that sense too that he hasn’t stopped trembling, that he continues to worry and fear for this child for numerous reasons.

What distinctions did you make between each of the sections in the book and how did you decide how to organize the poems?

A little bit is narrative. There is a movement too from the way I remember to sort of questioning my own memory at the end (of the book) especially as my son shows up and makes me rethink my world and my memories. It moves seasonally somewhat too. There’s this sense of movement through winter, especially, across this winter into summer. We have the first three sections before we finally get into the forth to birth, to arrival. The last one I think of as kind of a coda – it’s a single long poem – which is both sort of trying to look forward and to look back. It’s these letters written on the occasion of my son’s first birthday.